The workforce is smaller than it was before the pandemic. This is a problem because businesses need staff. To date, the focus has been on older (50+) people and a rise in their rate of inactivity. In this article, I want to focus on another group that is increasingly inactive – younger people (aged 16-24).

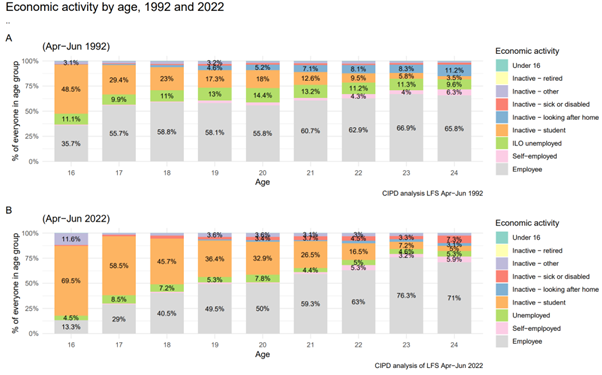

Inactivity is not always bad. Throughout one’s life there are periods of inactivity, most obviously at the beginning when people study, and at the end when people retire. However, in both these states, people are not participating in work and that has a cost. The opportunity cost of lost earnings and a cost to the economy of lower labour supply. Policies like increasing state pension age aim to reduce inactivity through retirement. However, much less attention is paid to inactivity of younger people. The chart below compares the economic activity of 16–24-year-olds, 30 years apart in 1992 and 2022.

The difference is striking. Most notable is the trend over time towards greater levels of inactivity due to study and a subsequent decrease in employment. There are also lower rates of unemployment too (which is significant as it means not only are there fewer young people working, but also fewer available and looking for work). Another interesting trend is the reduction in ‘looking after family and home’ which is significant in 1992, but almost entirely absent in the 2022 cohort. This perhaps represents a reduction in teenage pregnancy and a move to starting families later.

If we apply the 1992 economic activity rates to the 2022 rates, 16–24-year-old population, we can get an idea of how many people are no longer available to work because of these changes. The answer is close to a million people (913k). That is a huge reduction in potential workforce which is a cost (albeit one that we hope the increased investment in human capital will outweigh in benefits).

Could we have our cake and eat it?

Could we have all the benefits of education and young people in work too? People can do both, but the evidence suggests that they increasingly do not. In 2015 a Government sponsored report lamented the death of the Saturday job among teenagers. In 2008, 39% of students aged 16-24 had a job. By 2022 this had fallen to 34%. This is in part due to the collapse in part-time undergraduate students (who are more likely to be working), but there has also been a decline in the rate at which full-time students work (from 32% in 1993 to 29% today).

78% of part-time students also have a job. However, the proportion of part-time students has been falling - from 12% of 16–24-year-olds in 2008 to 10% in 2022. Note, as part-time students tend to be older (“mature” in the language of education) the collapse in part-time students more generally is much more precipitous than the subset of 16-24-year-olds this blog is concentrating on. Indeed, the dearth of second chances later makes the need to get it right the first time for younger people even greater. Part-time study enables those who need to work to study, but perhaps part-time study also enables those who need to study to work and as such curtailing opportunities for part-time study could be reducing labour supply.

Maybe young people focusing their energies exclusively on education is a rational strategy. With success in high-stakes exams meaning the difference between progressing to the preferred next stage or the second-best option. An A-level grade can mean the difference between a first-choice university or not, and a 2:1 is needed to get onto a grad scheme. The focus on study is rewarded with a greater payoff later. However, this does not make it an optimal system.

What’s more, it’s popular by Secretaries of State for Education amongst others, to suggest that at least one goal of education should be to prepare people for the world of work, and employment is perhaps the best way to do this. Other countries achieve much greater levels of study and work for younger people because of higher rates of apprenticeships which by their nature combine work and study.

Perhaps it is time to ask a more fundamental question. Is the front loading of human capital development at the beginning of one’s life and career the best strategy? The CIPD’s recent report on overqualification suggests that many young people are making the investment but not reaping the same returns, instead spending more time in lower-paid/lower-skilled work.

Our main argument

The key argument of this blog is that during labour shortages businesses and policymakers could be considering boosting employment of younger people, where to date the focus has been on older people. However, I suggest that people respond to incentives, and we may need to organise a skills system that facilitates working. Such a system would include:

- More opportunities for second chance catch-up, i.e., part-time study provision and the ability to access high quality, and free, flexible accredited learning opportunities to upskill or reskill.

- Less high-stakes system. This is one that perhaps the HR profession could help with by adopting university and grade-blind hiring practices.

- Boosting the number of apprenticeships for those under 25s. In recent years most of the growth in apprenticeships has gone to the 25+ group.

Note on dates

2008 is the first year that I could find a variable (CURED8) in the labour force survey that allowed me to identify part-time students (Thanks to Paul Bivand for pointing me in the right direction). The variable STUCUR which enables as to identify full-time students was only available from Oct-Dec 1993. The chart used data from Apr-Jun 1992 which is the first year that the labour force survey was done quarterly and provides a nice symmetry with Apr-Jun 2022 which is exactly 30 years later.

Topics A-Z

Browse our A–Z catalogue of information, guidance and resources covering all aspects of people practice.

Bullying

and harassment

Discover our practice guidance and recommendations to tackle bullying and harassment in the workplace.

About the author

Jon Boys, Labour Market Economist

Jon joined the CIPD in January 2019 as an Economist. He is an experienced labour market analyst with expertise in pay and conditions, education and skills, and productivity.

Jon primarily uses quantitative techniques to uncover insights in labour market data, both publicly available and generated through in house surveying. Jon regularly contributes commentary and analysis of economic issues on the world of work to online, print and TV media. Recent work includes the creation of an international ranking of work quality, analysis of firm level gender pay gap reporting data, and an ongoing programme of work looking at the changing age profile of the UK workforce.

Explore the CIPD’s point of view on age diversity in the workplace, including recommendations for employers and actions for the UK Government

This factsheet looks at recruiting overseas workers, the categories of non-UK nationals able to enter and work in the UK, and the legal framework involved.

Peter Cheese, the CIPD's chief executive, looks at the challenges and opportunities faced by today’s business leaders and the strategic priorities needed to drive future success

We outline the key pieces of legislation set to come into force in the UK and explain their implications for employers and employees

We examine people’s desired hours and how this compares to the hours they actually work

Employers’ reactions to pension proposal highlight concerns over cost, while the CIPD calls for focus on raising pension awareness among staff, the need for higher contributions and better understanding of value for money